Revisiting an old format: the wordless book.

Wordless comics are rare. Yet, this visual language offers a wide range of possibilities to explore, for instance:

Contemplative stories

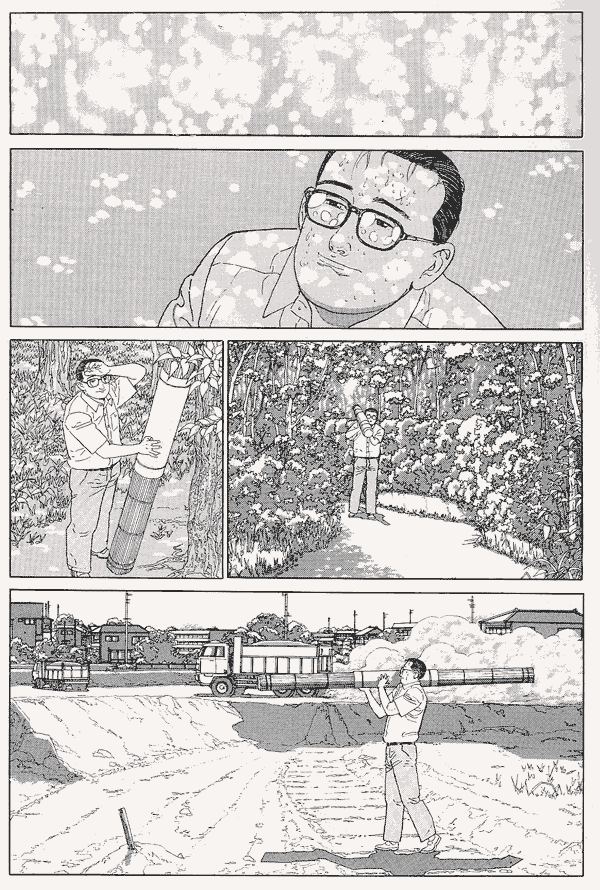

Contemplative stories are visual by nature. Aruku Hito — 歩くひと, a manga that tells a long-form story with next to no words is a fine example. Translated into English as The Walking Man and in French as L’Homme qui Marche.

Dreamlike stories

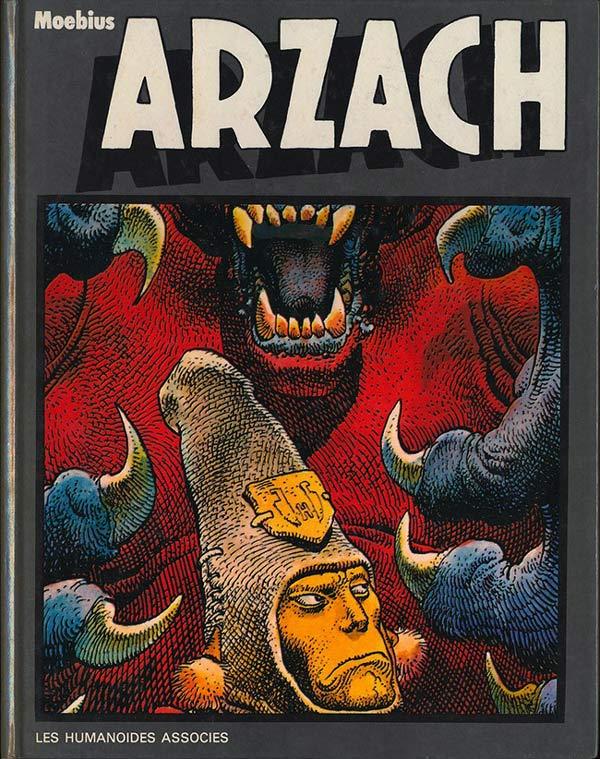

Stories that explore the ”mindscape” of the subconscious. In this genre, impossible to leave out Arzach1, a magnificent silent comic, published in 1975. Its sheer force inspired and will continue to inspire generations of illustrators.

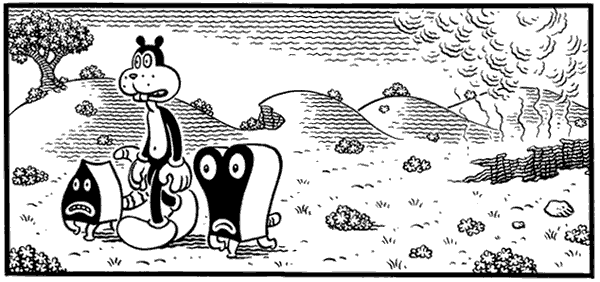

Quasi-wordless, Jim Woodring’s Frank books are another extraordinary example. Frank’s adventures happen in a self-contained startling world, surreal, and at times eerie.

Visual poetry

I don’t know what visual poetry is, don’t ask me, but it exists. In this genre, sequences of images are at work, regardless of any meaningful storyline.

Children books

Wordless books have a rich tradition that predates comics. In recent years, (long-form) wordless comics aimed at youths began to resurface. Though not limited to preschool years, these books are a logical step for kids who have yet to learn reading.

Alternative comics

Wordless stories addressing adult themes such as Gegika, or “dramatic picture books”, as coined by the late Yoshihiro Tatsumi. Graphic novels, Nouvelle Manga, and Fusion Comics. All these genres push visual narration forward.

Action

Fast-paced sequences rendered in extreme slow-motion are perfect for wordless comics. With a lot of “cuts” for a single scene, they look close to a detailed film storyboard. This cinematic stylistic technique is sometimes referred to as decompression in comics.

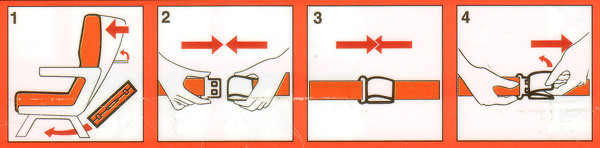

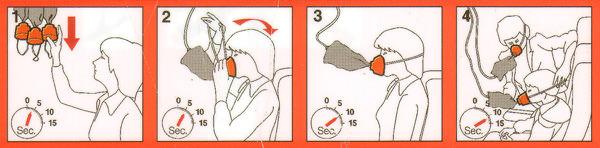

Explanatory and didactic

Comics that work as info-graphics. Companies sometimes use these in their communication charts and how-to guides. Technical manuals, infographics, plane emergency leaflets, and warning signs are typical examples. But it could also work for a martial art manual, any book involving learning movement, like dance or gymnastics, and synchronization skills, like in choreography.

Scientific vulgarisation

Comics can help to present complex subjects with a deeper cognitive dimension. The borders between literacy and visual literacy2 blur. Both can be essential to learning.

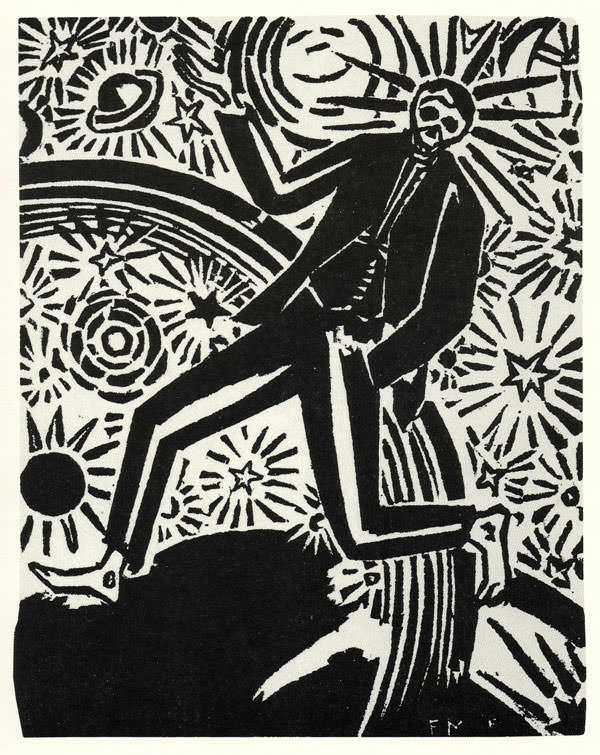

Propaganda and Pamphlets

With their straightforward visual nature, wordless comics are well suited for propaganda and pamphlets. The first wordless novels appeared in close association with protest movements during the 20’ and 30’. Their topics were war, social injustice, and rebellion. Artists like Frans Masereel were eager to address social commentary and controversial themes. At their time of publication, wordless novels were popular, reaching a large audience3. Woodcut’s economy of lines, coupled with the absence of text made wordless novels an ideal medium to reach the masses.

Advertising

As we see, visuals can have way more impact than words. Advertisers love to use the same graphic language than activists, to other ends. In fact, they often each repurpose one another’s codes. There are countless examples of advertising using visual only, as well as of comics used in advertising. Yet I have never seen a wordless comic in an advertisement. Advertising tries to make the most of a medium, and it is rare to see a print ad without a copy or a poster without a tagline. If you reduce a corporate message to its essence, you reach a point where there is only a brand mark left. Thus the best way to use wordless comics for an ad would be creating a sequential story based on a logo.

With so much potential, why are there so few?

First, rarity is relative. There are many wordless comics in circulation already. And new artists keep rejuvenating the form. Yet only a small percentage of the total comics published each year don’t use words. Somehow wordless comics are still less expected. For most people, the combination of words and pictures is what makes comics. Definitions aside, readers expect picture and words. We are still in a culture where verbal communication takes the primacy over image4. Even if images are omnipresent and perhaps more direct. In this context, wordless comics might seem arcane, less attractive to readers. But are they also less efficient at telling stories?

If the answer is yes, it leads to another explanation. It is hard to find good ones because it is hard to create them in the first place. The literacy rate is high enough that the demand for such stories is no longer mainstream—if it ever was. We can look for correspondence with silent films and wordless novels. But the landscape has changed. There are no longer just books, no more cinema. Those times are gone. Now everything is supposed to be entertainment. Creating a good wordless comic today means competing with sophisticated mediums. Digital comics, print, film, video games, TV, web and computer animation, even virtual reality.

Narrative challenges

From a narrative perspective, rarity highlights how difficult it is to make wordless stories work. For all its apparent simplicity, it is a form that calls for sustained attention. At a time of information overload, compulsive reading, zapping and multimedia disruption, attention is the scarcest resource5. This is especially true for long-form. Short form comics, with a few panels in a single strip, are widespread and thrive on the web. Indeed, strips or cartoon are an ideal format for the web’s quick consumption mode. They excel at grabbing the shortening attention span of online readers6. Whereas long-form visual narrative cannot depend on text to save a poor picture. Images must keep the viewer interested without the help of text. Intricate or minimal, pictures alone must steer the reader’s curiosity. Frame by frame for an entire story.

Things pictures cannot say.

A picture is worth a thousand words

One showing is worth a hundred sayings

The history of a picture’s worth, shows the rise of a fake proverb, coming from advertising. However, that idea was present in literature for a longer time:

A picture shows me at a glance what it takes dozens of pages of a book to expound. —IVAN TURGENEV

All these, in essence, summarise “show, don’t tell”.

There are counter sayings:

As the Chinese say, 1001 words is worth more than a picture. —JOHN McCARTHY

Pictures are worth like a thousand words max. An alphabet can make up a bazillion words. —DAN HARMON

For all the sayings, there is a surprising amount of things you cannot tell with pictures alone. Words can convey better or with less effort than imagery a lot of subtle, intangible things. For instance, dialogues, summaries, time and place indications. Captions driving the story forward. To create a wordless story you have to replace a lot of written information by pictures. Silent films found a partial solution to this limitation with the title card. But silent films have at least two things that wordless comics lack: movement and soundtrack7. Both are expression and emotion amplifiers. Compared to Cinema, comics is a simpler medium. Wordless comics are even more minimal. But here too, the comparison falls short: there are stories one can never tell with a certain medium, and stories best for a particular form.

I always feel that to adapt a comic-book story into a live-action picture is a mistake. The two look similar only on the surface, but at heart, they are truly different. (…) Cinema is movement. Comics are immobility. Comics create movement from immobility. The genius of comics is that they force the reader to create movement. —ALEXANDRO JODOROWSKY

Wordless comics call for a different form of reading. The reader is no longer required to read but derives a story interpretation from watching static images series. Can narrative limitation rejuvenate the form? The musicality of words, onomatopoeia, and annotations are lost but only to offer a different experience.

Visual literacy

One of the main advantages of telling a story through visuals-only is universality. Imagine a story anyone can understand anywhere, without any language barrier. Yet different cultural codes are at play in American, European and Japanese comics. Visual languages differ between cultures. Neil Cohn8 studies show striking disparities in visual literacy9 across cultures. Today we live in a visual era, yet words still prevail over images, and visual literacy tends to be overlooked. The case for using words to communicate is strong even if they leave a lot to interpretation. Words are everyday language, with which we communicate despite their limitation. Whereas films and comics stories come with defined imagery that leaves less to the imagination of their audience than would a book of fiction. Even predominantly visual works such as films and comics often originate in words (a scenario, script or screenplay).

The Future of wordless comics

Visual narrative / visual storytelling

For this simple, next to a primitive art form to be successful, it must tell a good story. A story nobody has ever seen before, or an old one, told from a new perspective. Compelling imagery is not enough. Imagine sitting and watching a slideshow of beautiful images. How boring. Building a mercurial story to take the reader (watcher) by surprise requires more. Optimal clarity is imperative to capture and keep the viewer’s interest. What do your pictures mean? Your audience shouldn’t have to do any guesswork to find out. You can still use hermetic visual clues but only if it serves a purpose within the story.

Wordless comics offer a simple, different form of reading. Time and pace are still paramount to narrative success and satisfactory reading. As a wordless comics reader, you must still be in control of your reading pace to engage and immerse in the story. But reading pictures call for a different kind of effort on your part. In the absence of text, you might have to linger over the pictures a little more to understand what’s going on.

Pure visual storytelling in long-form without complex paneling or fancy comics tricks is quite a challenge. It is about taking the most minimal resource to maximal effect. Telling a story with a succession of images in a single panel ratio from beginning to end. Just as a writer creates a whole world in the mind of the reader, with nothing else but words.

Despite or thanks to their limitations, there is more to wordless comics than meet the eye. Watch this space.

Further reads:

The Walking Man by Jiro Taniguchi

Arzach by Moebius — The first edition (Les Humanoides Associés) of this masterpiece is unfortunately out of print.

The Frank Book by Jim Woodring

Gon ゴン (漫画) by Masashi Tanaka

Graphic Witness: Four Wordless Graphic Novels by Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, Giacomo Patri and Laurence Hyde

The Visual Language of Comics: Introduction to the Structure and Cognition of Sequential Images. (Continuum Advances in Semiotics) by Neil Cohn

The Language of Comics: Word and Image by by Robin Varnum (Editor), Christina T. Gibbons (Editor)

Footnotes:

Philippe Lefèvre-Vakana. “à la recherche d’un chef-d’œuvre de Raymond Poïvet” (in French, 2003, revised, 2011) Accessed December 28, 2014. http://neuviemeart.citebd.org/spip.php?article437

Jessie Bi. “La bande dessinée muette” D9 (in French, June 2006) Accessed April 2, 2014. http://www.du9.org/dossier/bande-dessinee-muette-1-la/

ImageTexT — Interdisciplinary Comics Studies http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/

David Robson. “Are we hard-wired to doodle?” (October 2014) Accessed October 1, 2014 http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20140930-are-we-hardwired-to-doodle

Steven Brower. “The Advertising Power of Comic Book Artists” (April 25, 2012) Accessed May 23, 2015 http://www.printmag.com/illustration/the-advertising-power-of-comic-book-artists/

-

Moebius said of Arzach, that he wanted “to bridge two insulated (airtight) worlds. That, humble, realist, of comic books, and that, immense and creative, of Art”. Raymond Poïvet’s wordless graphic novel M.I.X. 315 plays with the same concept. Watch M.I.X. 315, reproduced online with permission by neuvièmeart 2.0. It looks like these pages played an inspirational role in the creation of Arzach. ↩

-

For example, the German edition of Masereel’s Passionate Journey, Mein Stundenbuch: 165 Holzschnitte surpassed 100 000 copies in sales in Germany through several reprints. ↩

-

This is changing. Cinema, television, and later the worldwide web created a cultural shift toward the visual over the verbal and textual, in the last century. Even the printed press, to some extend, became more reliant on images. The advent of the mobile web accelerated this tendency. Visual (video + images) usage continues to rise. This is likely to continue with the coming age of immersive gaming, augmented reality and virtual reality. ↩

-

“A visitor’s default behaviour isn’t to read every word, it’s to leave” — Tony Haile. ↩

-

Tom Chatfield, Aeon, “The attention economy” Accessed May 31, 2016. https://aeon.co/essays/does-each-click-of-attention-cost-a-bit-of-ourselves ↩

-

Digital comics have seen the emergence of accompanying sound or music, with mixed results. ↩

-

Neil Cohn. “Downloadable papers on visual language research” http://www.visuallanguagelab.com/papers.html. ↩

-

“Framing ‘I can’t draw’: The influence of cultural frames on the development of drawing” http://www.visuallanguagelab.com/P/NC_drawingframes.pdf. ↩